Retro gaming royalty Dan Wood joins The Escapist with the first of his new weekly columns. You can read Dan each and every Saturday right here and catch up with him more often on his YouTube channel.

One of the biggest stories in the world of retro recently has been the surprise resurrection of the company Commodore. For those too young to remember (or possibly too old and whose memory is failing), Commodore was the company responsible for giving a whole generation of Gen Xers and elder Millennials their first taste of computing, and their legendary Commodore 64 computer still holds the title of “the best-selling computer of all time” (if you look at it through the lens of single-model systems, and mostly ignore the Raspberry Pi).

The 1980s “playground wars” between kids who owned a C64 or a Sinclair ZX Spectrum are still the stuff of legends. Rather ironically, both systems were brought back around the same time in 2025 with the release of new spins on the legendary machines based on FPGA technology.

Sinclair fans got the third Kickstarter of the awesome ZX Spectrum Next, a souped-up, turbo-charged version of the classic machine with some huge expansions, and likewise Commodore fans got the new Commodore 64 Ultimate. Many (like me) were lucky enough to find one under their Christmas tree last month.

Between the ages of 7 and 14, unwrapping a Commodore product for Christmas was a tradition in our house, and before you say I was spoiled, these weren’t always computers. Some years it might have been a disk drive or a new mouse, but the Christmases when my Commodore Plus/4, my brother’s Commodore 64, and my Amiga 500 turned up are some of the happiest festive memories I have.

Even seeing a new box embossed with the legendary “chicken head” Commodore logo (so called because the C= looks like a chicken’s head with a beak if you squint the right way) took me back, and using the C64 Ultimate felt every bit like using a classic Commodore 64 from the 1980s. I was transported back to sitting in my best friend Shaun’s bedroom playing games like Kikstart, IK+ and California Games after school on a hot late-80s summer day, with our BMXes on the front lawn and New Order blasting out of the radio, and any other rose-tinted clichés you want to throw in. Although in reality, Shaun’s mum likely brought the BMXs immediately inside as they would have been TWOCed within minutes on the rough Middlesbrough estate we lived on at the time, and it was probably something like Sonia playing on the radio. Nostalgia is a funny thing.

Although the 21st-century reboot of the machine comes with a few modern conveniences that are very much appreciated, nobody wants to sit for ten minutes praying that a game will load from an unreliable cassette tape. I might be into retro, but I’m not a masochist. So having features hidden away discreetly, like a USB port so you can load your games from a memory stick, or network connectivity to share files over your Wi-Fi, is a “good thing”, and you don’t really notice them until you need them.

Retro modern experience

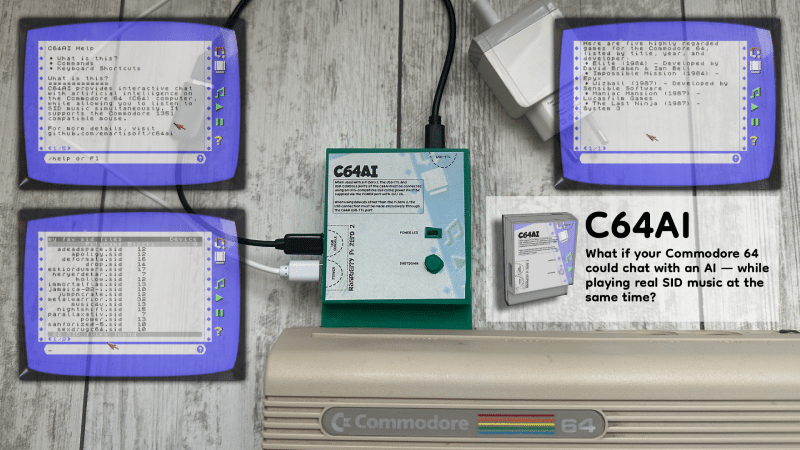

This also brings a semblance of the modern world to the retro experience, and one which stirred up some conflicting emotions in me. When I was browsing some of the new games and software people are producing for the platform (yes, there is still a huge active development scene for this system), one of the tools I found was a project called C64AI. This solution allows you to talk to ChatGPT via your Commodore 64 whilst listening to some banging chip tunes generated by the computer’s legendary SID audio processor.

I spotted this in one of the many Commodore 64 users’ Facebook groups, and as you can imagine, it sparked quite a reaction, from people thinking it was an interesting idea to the majority insisting we “keep AI slop” away from our retro systems!

Retro AI

This unease also resonated with me, which surprised me. I consider myself an enthusiastic proponent of AI. I have monthly subscriptions to ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude. I use it daily for work and brainstorming, I run local AI models on my computers, and I’ve even dipped my toe into “vibe coding” lately. But AI invading the safe space that is retro made me feel a bit uneasy.

AI has been slowly creeping its way into retro gaming over the past year or two. I purchased an indie game for the Amiga (another of Commodore’s classic systems) called Tale of Evil. It’s a fantastic top-down action game, but it has received some criticism as it heavily features AI-generated graphics and even a fully AI-created soundtrack.

Although it can’t be denied there is a lot of “AI fatigue” at the moment, I think it goes deeper than that. Enjoying retro games and systems is supposed to feel like a place where you can step outside modern technology entirely. I may have modern conveniences like a flash cart of ROMs plugged into my Sega Mega Drive, but there’s no algorithm watching how long I spend on each title and trying to learn my habits.

More human

That’s a big part of why retro holds such appeal. It isn’t just about old hardware or pixel art, it’s about a slower, more human way of interacting with technology. Games were created within obvious limitations, often by very small teams, and those constraints shaped the final experience in ways that still feel distinctive. In that context, the arrival of AI feels jarring, not because it’s new, but because it belongs so firmly to the modern world we’re often trying to escape.

And yet, retro gaming has never been frozen in time. We’ve already made peace with plenty of modern inventions, provided they stay politely out of the way. FPGA systems recreate old hardware with astonishing accuracy. Flash cartridges replace shelves of old media. HDMI outputs, USB ports and Wi-Fi connectivity are all quietly welcomed as long as they don’t interfere with the illusion.

At the same time, it’s hard to ignore the practical reality. Many modern retro projects are built by tiny teams or even a lone ‘bedroom coder’. Expecting everyone to be a fantastic programmer, artist and composer all at once is unrealistic. If AI tools allow more people to create games for classic platforms, does that dilute the scene, or does it expand it? Does it matter if a sprite was generated in an AI art model rather than drawn in Deluxe Paint on an old Amiga 500 if the end result is still playable and fun?

Perhaps the real discomfort comes from the fact that AI forces us to define what we think retro actually is. If retro is about preserving a moment in time, then AI feels like an intrusion. If it’s about experiencing old systems in new ways, then maybe it’s just a new tool being brought into the fold. Retro has always evolved, even if some prefer to pretend otherwise.

I don’t think we’ve worked out where that line should be yet, and maybe that’s okay. Retro gaming has always thrived on debate, experimentation and a healthy amount of stubbornness. The arrival of AI doesn’t suddenly invalidate the culture, but maybe it does challenge us to think more carefully about what we’re trying to protect, and why.

The post Retro gaming was an escape. What happens when AI turns up? appeared first on The Escapist.