Text rendering is cursed. Anyone who has worked on text will tell you the

same; whether it’s about layout, bi-directional, shaping, Unicode, or the

rendering itself, it’s never a completely solved problem. In my personal case,

I’ve been working on trying to render text in the context of a compositing

engine for creative content. I needed crazy text effects, and I needed them to

be reasonably fast, which implied working with the GPU as much as possible. The

distance field was an obvious requirement because it unlocks anti-aliasing and

the ability to make many great effects for basically free.

In this article, we will see how to compute signed distance field on the GPU

because it’s much faster than doing it on the CPU, especially when targeting

mobile devices. We will make the algorithm decently fast, then after lamenting

about the limitations, we will see what kind of effects this opens up.

Extraction of glyph outlines

Non-bitmap fonts contain glyphs defined by outlines made of closed sequences

of lines and (quadratic or cubic) Bézier curves. Extracting them isn’t exactly

complicated: FreeType or ttf-parser typically expose a way to do that.

For the purpose of this article, we’re going to hard code the list of the Bézier

curves inside the shader, but of course in a more serious setup those would be

uploaded through storage buffers or similar.

Using this tiny program, a glyph can be dumped as series of

outlines into a fixed size array:

struct Bezier {

vec2 p0; // start point

vec2 p1; // control point 1

vec2 p2; // control point 2

vec2 p3; // end point

};

#define N 42

#define NC 2

const int glyph_A_count[2] = int[](33, 9);

const Bezier glyph_A[42] = Bezier[](

Bezier(vec2( 0.365370, -0.570817), vec2( 0.374708, -0.631518), vec2( 0.332685, -0.687549), vec2( 0.339689, -0.748249)),

Bezier(vec2( 0.339689, -0.748249), vec2( 0.339689, -0.748249), vec2( 0.344358, -0.764591), vec2( 0.351362, -0.771595)),

Bezier(vec2( 0.351362, -0.771595), vec2( 0.384047, -0.822957), vec2( 0.402724, -0.855642), vec2( 0.442412, -0.885992)),

// ...

);

glyph_A_count contains how many Bézier curves there is for each sub-shape

composing the glyph, and glyph_A contains that list of Bézier cubic curves.

Even though glyphs are also composed of lines and quadratic curves, we expand

them all into cubics: “who can do more can do less”.

We use these formulas to respectively expand lines and quadratics into cubics:

\begin{aligned}

B_1 &= \begin{bmatrix}

P_0 \\

\mathrm{mix}(P_0, P_1, 1/3) \\

\mathrm{mix}(P_0, P_1, 2/3) \\

P_1

\end{bmatrix} \\

B_2 &= \begin{bmatrix}

P_0 \\

\mathrm{mix}(P_0, P_1, 2/3) \\

\mathrm{mix}(P_1, P_2, 1/3) \\

P_2

\end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}

Where P_n are the Bézier control points.

For simplicity and because we want to make sure the most complex case is well

tested, we will stick to this approach in this article. But it also means there

is a lot of room for further optimizations. Since solving linear and quadratics

is much simpler, this is left as an exercise for the reader.

Warning

You may be tempted to upload the polynomial form of these curves directly to

save some computation in the shader. Don’t. You will lose the exact

stitching property because one evaluated polynomial end B_n(1) will

not necessary match the next polynomial start B_{n+1}(0). This makes

artificial “precision holes” that will break rendering in obscure ways.

Signed distance to the shape

In the previous article, we saw how to get the distance to

a cubic Bézier curve. Each glyph being composed of multiple outlines, we can

simply run over all of them and pick the shortest distance.

float get_distance(vec2 p, Bezier buf[N], int counts[NC]) {

int base = 0;

float dist = 1e38;

for (int j = 0; j < NC; j++) {

int count = counts[j];

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

Bezier b = buf[base + i];

float d = bezier_sq(p, b.p0, b.p1, b.p2, b.p3);

dist = min(dist, d);

}

base += count;

}

return sqrt(dist);

}

Where bezier_sq() is the distance to the Bézier curve, squared, as defined in

the previous article.

This works just fine, but as you can imagine, it’s not cheap to solve so many

distances per pixel. A first straightforward optimization would be to ignore any

curve with a bounding box further than our currently best distance, because none

of them can give a shorter one:

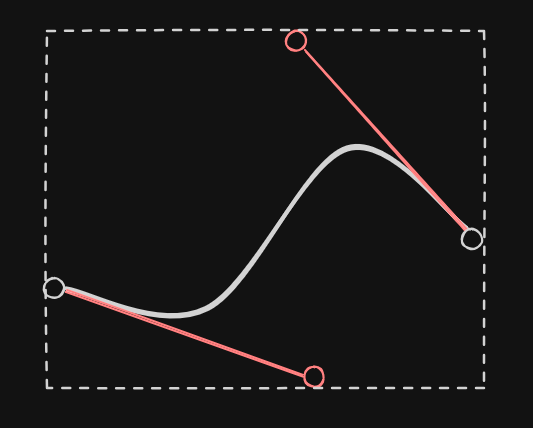

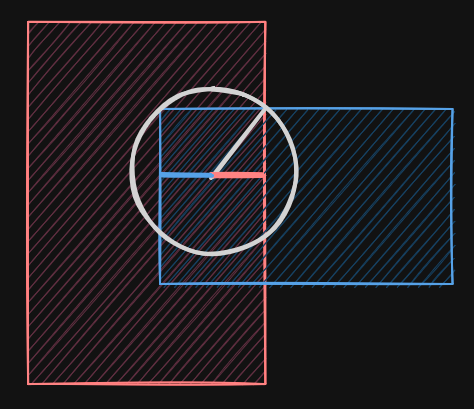

Where each box encloses a Bézier curve like this:

We could use a tighter bound but it would require more computation so this felt

like a good trade-off.

Implementing this in the inner loop is pretty simple:

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

Bezier b = buf[base + i];

vec2 p0=b.p0, p1=b.p1, p2=b.p2, p3=b.p3;

// Distance to box (0 if inside), squared

vec2 q0 = min(p0, min(p1, min(p2, p3)));

vec2 q1 = max(p0, max(p1, max(p2, p3)));

vec2 v = max(abs(q0+q1-p-p)-q1+q0, 0.)*.5;

float h = dot(v,v);

// We can't get a shorter distance than h if we were to compute the

// distance to that curve

if (h > dist)

continue;

float d = bezier_sq(p, p0, p1, p2, p3);

dist = min(dist, d);

}

The distance to the bounding box formula comes from this explicative video by

Inigo Quilez (the basic one, without the inside distance), adapted to

the Bézier control point coordinates.

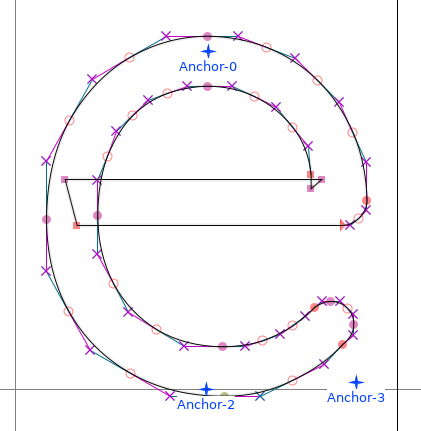

This saves a lot of computation in certain cases, but the worst case is still

pretty terrible, as shown by the heat map of this ‘C’ glyph:

Indeed sometimes, it takes a long time to reach a good Bézier curve that is

small enough to disregard most of the others. We observe it the further we go

away from the beginning of the shape.

So the next step is to find a good initial candidate. One cheap way to do that

is to first compute the distance to the center point of each curve, and pick

the smallest:

// Find a good initial guess

int best = 0;

float boxd = 1e38;

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

Bezier b = buf[base + i];

vec2 p0=b.p0, p1=b.p1, p2=b.p2, p3=b.p3;

vec2 q0 = min(p0, min(p1, min(p2, p3)));

vec2 q1 = max(p0, max(p1, max(p2, p3)));

vec2 v = (q0+q1)*.5 - p;

float h = dot(v,v);

if (h < boxd)

best=i, boxd=h;

}

// Initial guess

Bezier bb = buf[base + best];

dist = min(dist, bezier_sq(p, bb.p0, bb.p1, bb.p2, bb.p3));

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

if (i == best) // We already computed this one

continue;

Bezier b = buf[base + i];

vec2 p0=b.p0, p1=b.p1, p2=b.p2, p3=b.p3;

// ...

This optimization is immediately reflected on the heat map, where only the

central point seems to become a critical point (this glyph is a pathological

case as it forms a circle):

Winding number

The last step is to figure out whether we are inside or outside the shape. There

are two schools here, the even-odd and the non-zero rules. We’ll pick the

latter because that’s the expectation in the case of font rendering.

In deconstructing Bézier curves, we explained the theory of that

specific algorithm so we’re not going to dive into the details again. The basic

idea is to strike a ray in one direction from our current position, and get

how many times we cross a given curve. Here we will arbitrarily choose a

horizontal ray line y = P_y where P is our current coordinate.

The topology of each curve can hint us on whether it’s worth considering it or

not. For example, if every control point is above or below our current position,

it can be ignored. We can store all the signs in a mask and bail out as soon

as the ray is either completely below or completely above the bounding box of

the curve:

int signs = int(p0.y < p.y)

| int(p1.y < p.y) << 1

| int(p2.y < p.y) << 2

| int(p3.y < p.y) << 3;

if (signs == 0 || signs == 15) // all signs are identical

return 0;

Each sign indicates the position of the control point with regard to the ray.

We can use the relative position of the starting point as a reference for the

overall orientation (if there is a crossing, we know it will come from below

or above):

int inc = (signs & 1) == 0 ? 1 : -1;

We also need to convert the Bézier curves to the usual polynomial

at^3+bt^2+ct+d:

vec2 a = -p0 + 3.*(p1 - p2) + p3,

b = 3. * (p0 - 2.*p1 + p2),

c = 3. * (p1 - p0),

d = p0 - p;

Then we can find the y-roots and check every point on the x-axis. For every

crossing point (at most 3), we switch the sign:

float r[5];

int count = root_find3(r, a.y, b.y, c.y, d.y);

vec3 t = vec3(r[0], r[1], r[2]);

vec3 v = ((a.x*t + b.x)*t + c.x)*t + d.x;

if (count > 0 && v.x >= 0.) w += inc;

if (count > 1 && v.y >= 0.) w -= inc;

if (count > 2 && v.z >= 0.) w += inc;

Since we already have a 5th degree root finder from the previous article, we

just have to build a tiny version for the 3rd degree:

int root_find3(out float r[5], float a, float b, float c, float d) {

float r2[5];

int n = root_find2(r2, 3.*a, b+b, c);

return cy_find5(r, r2, n, 0., 0., a, b, c, d);

}

Note

Our root finder doesn’t return roots outside [0,1] so no filtering is

required.

To summarize:

int bezier_winding(vec2 p, vec2 p0, vec2 p1, vec2 p2, vec2 p3) {

int w = 0;

int signs = int(p0.y < p.y)

| int(p1.y < p.y) << 1

| int(p2.y < p.y) << 2

| int(p3.y < p.y) << 3;

if (signs == 0 || signs == 15)

return 0;

int inc = (signs & 1) == 0 ? 1 : -1;

vec2 a = -p0 + 3.*(p1 - p2) + p3,

b = 3. * (p0 - 2.*p1 + p2),

c = 3. * (p1 - p0),

d = p0 - p;

float r[5];

int count = root_find3(r, a.y, b.y, c.y, d.y);

vec3 t = vec3(r[0], r[1], r[2]);

vec3 v = ((a.x*t + b.x)*t + c.x)*t + d.x;

if (count > 0 && v.x >= 0.) w += inc;

if (count > 1 && v.y >= 0.) w -= inc;

if (count > 2 && v.z >= 0.) w += inc;

return w;

}

For every sub-shape, we can accumulate the winding number, and use it at the end

to decide whether we’re inside or outside:

float get_distance(vec2 p, Bezier buf[N], int counts[NC]) {

int w = 0;

int base = 0;

float dist = 1e38;

for (int j = 0; j < NC; j++) {

int count = counts[j];

// Get the sign of the distance

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

Bezier b = buf[base + i];

w += bezier_winding(p, b.p0, b.p1, b.p2, b.p3);

}

// ...

}

// Positive outside, negative inside

return (w != 0 ? -1. : 1.) * sqrt(dist);

}

And voilà:

Warning

This winding number logic might be too fragile: it doesn’t cover potential

degenerate cases such as horizontal tangents / duplicated roots. But for

some reason, while I fought these issues for years, none of the weird corner

cases seemed to glitch in my extensive tests, probably because the root

finder is more resilient than what I was using before.

Limitations

Wicked curves

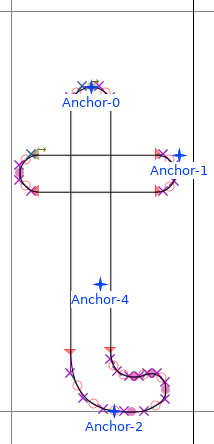

This may look satisfying, but it’s only the beginning of the problems. For

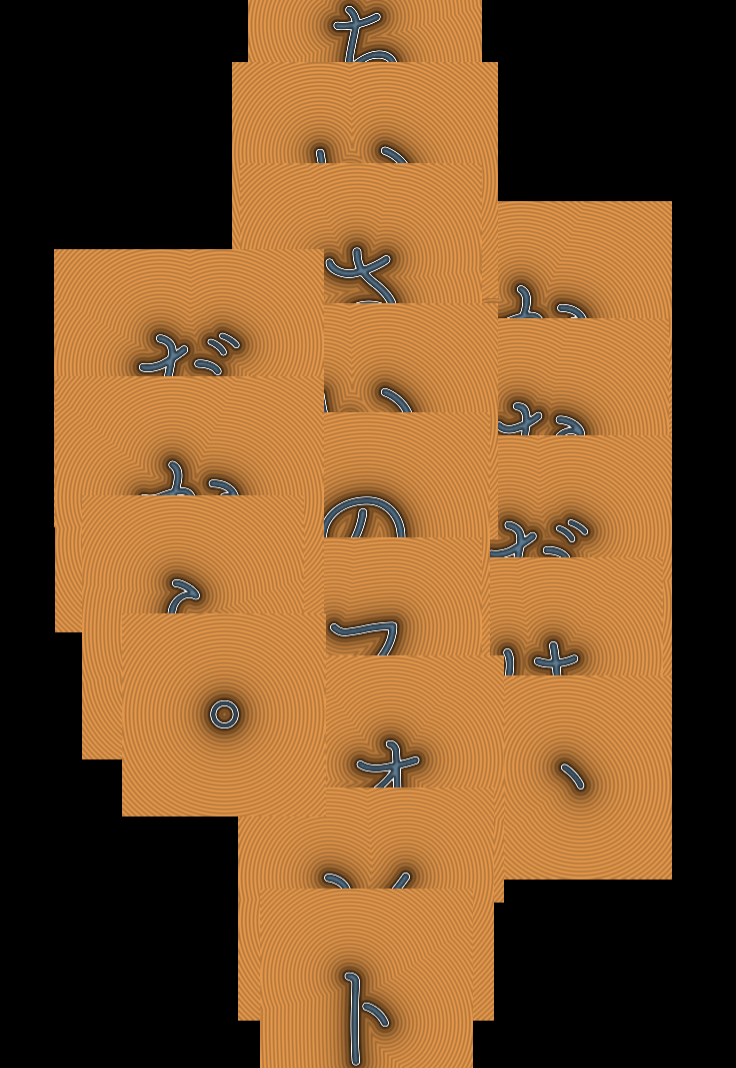

example, variadic fonts are typically following chaotic patterns:

In addition to the self overlapping part, notice the reverse folding triangle on

the right.

This completely wreck the distance field:

Even with a simple character display (meaning something that doesn’t exploit the

wide range of effects available with an SDF), it starts to glitch:

Little “cracks” should appears around the overlaps. This can be mitigated by

lowering the distance by a tiny constant to avoid the zero-crossing, but it

impacts the overall glyph (it gets more bold).

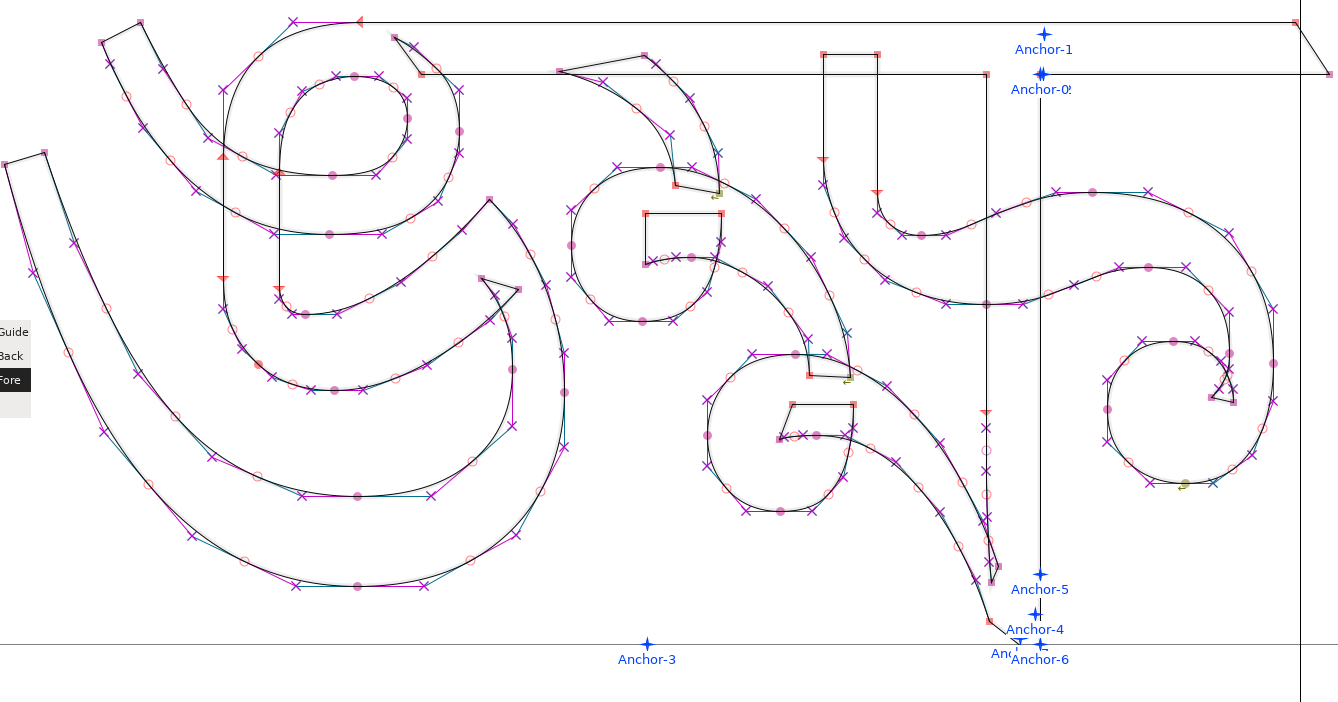

And it’s not just because of variadic problem, sometimes designers rely on

overlaps for simplicity:

And sometimes… well let’s say they have a legitimate reason to do it:

This is not something that can be addressed easily.

For example, take these two overlapping shapes:

We see that the actual distance (white circle) is not the smallest distance

to either shape, and it’s not even the smallest distance to any edge: it is at

an intersection point between two curves, which we do not have. Here we’re

dealing with line segments, but with cubic curves, the problem explodes in

complexity.

At this point, we need another strategy, like feeding the GPU renderer with

preprocessed outline-only curves. Many people rely on curves flattening to

address this issue. This is unfortunately yet another field of research that

we’re not going to explore this time.

Inigo talked about the combination of signed distance if you want

some ideas, but aside from the first one (giving up), none seems particularly

applicable here.

Atlas and overlapping distances

Some effects such as blur or glow expand beyond the boundaries of the

characters, so the distance field needs to be larger than the glyph itself. This

means when an effect spread too large, there will be an overlap. If we’re making

an effect on a word, the distance field must be the unified version of all the

word glyphs (or sometimes even the sentence). The classic approach of an atlas

of glyph distances will not work reliably.

In the following illustration, a geometry per glyph is used, each geometry is

enlarged to account for the larger distance field, and we end up with potential

overlaps when applying effects.

Rounded corners

Like all distance maps, it suffers from the same limitations. The most common

one is the rounded corners problem. This is typically addressed using a

multi-channel signed distance field generator, but it’s hard for me

to tell how accessible it is for a portage on the GPU.

Note

This problem only appears with intermediate textures. When computing exact

distances like here directly in the shaders, this is not an issue.

Effects

Despite all these limitations, we can already do so much, so let’s close this

article on a positive note. This is not done here, but all of these effects are

free as soon as we have the distance field stored in an intermediate texture.

First, we have anti-aliasing / blur:

I wrote a dedicated article on the subject of AA (and blur) on SDF if you

want more information on how to achieve that.

The shape can also be drastically altered with a simple operator such as

“rounding”:

d -= rounding;

This is the same technique we suggested to cover up for the overlap glitch

earlier, just rebranded as an effect.

In the same spirit we can also create an outline stroke (on the outer edge to

preserve the original glyph design):

This is sooo useful because it makes it possible for our text to be visible no

matter what the background is. So many editors don’t have this feature because

it’s hard and expensive to do correctly. Given a distance field though, all we

have to do is this (which also includes anti-aliasing on every border):

float aa = fwidth(d); // pixel width estimates

float w = aa * .5; // half diffuse width

vec2 b = vec2(0,1)*outline - d; // inner and outer boundaries; vec2(-1,0) for inner, vec2(-.5,.5) for centered

float inner_mask = smoothstep(-w, w, b.x); // cut-off between the outline and the outside (whole shape w/ outline)

float outer_mask = smoothstep(-w, w, b.y); // cut-off between the fill color and the outline (whole shape w/o outline)

float outline_mask = outer_mask - inner_mask;

vec3 o = (inner_color*inner_mask + outline_color*outline_mask) * outer_mask;

We can also dig into our character with d = abs(d)-ring:

And maybe apply some glow to create a neon effect:

float glow_power = glow * exp(-max(d, 0.) * 10.);

o += glow_color * glow_power;

We could also do drop shadows, all sorts of distortions, or so many other

creative way exploiting this distance. You get the idea: it is fundamental as

soon as you want fast visual effects.

Conclusion

This article is the last of the series on 2D rendering for me. I’ve wanted

to share this experience and knowledge after many years of struggling (mostly

alone) on these issues. I wish I could have succeeded in providing a good free

and open-source text effects rendering engine to compete with the industry

standards. (Un)fortunately for me, the adventure stops here, but I hope this

will benefit creators and future tinkerers interested in the subject.

For updates and more frequent content you can follow me on

Mastodon. Feel also free to subscribe to the

RSS in order to be notified of new write-ups. It is also usually

possible to reach me through other means (check the footer below). Finally,

discussions on some of the articles can sometimes be found on HackerNews,

Lobste.rs and Reddit.